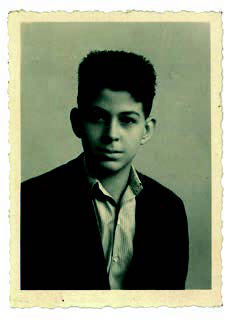

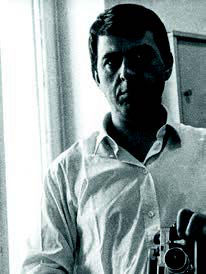

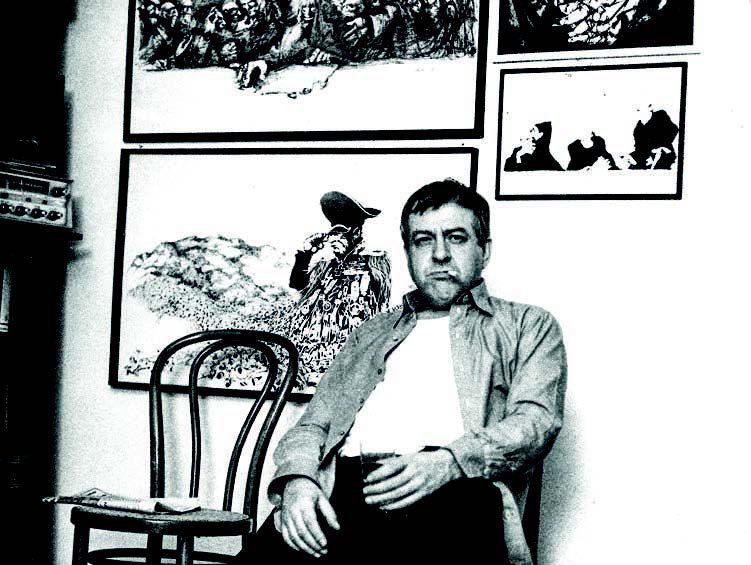

Maurizio Bovarini was a quite extraordinary and highly prolific illustrator. He was also, at least on the surface, indifferent to the myriad tricks of the publishing trade that make it possible for an author or an artist to ensure that their name will go down in history. Since he makes only the rarest of appearances in the canonical history of cartoons and illustration, the task of reconstructing his biography necessitated the collating of information supplied first-hand by his family: his wife Adele and his children, Andrea and Alessandra. Family is a story, but also an archive – in this case, a comprehensive archive that reveals what the illustrator was all about. Indeed, his bountiful output encapsulated thousands of illustrations; sketches, pencil drawings, drawings both large and small on poster board; works in fountain pen and marker; torn photographs around which he built images; cartoon panels and comic strips. Maurizio Bovarini was born in Bergamo, in the time-honoured quarters of the lower part of the town, on 31 July 1934. He lived in Piazza Pontida, the only square in Bergamo to have its own self-proclaimed Duke, and the backdrop to the annual “rasgamènt de la ègia”, a legacy of the pagan past, complete with bonfires lit half-way through Lent.